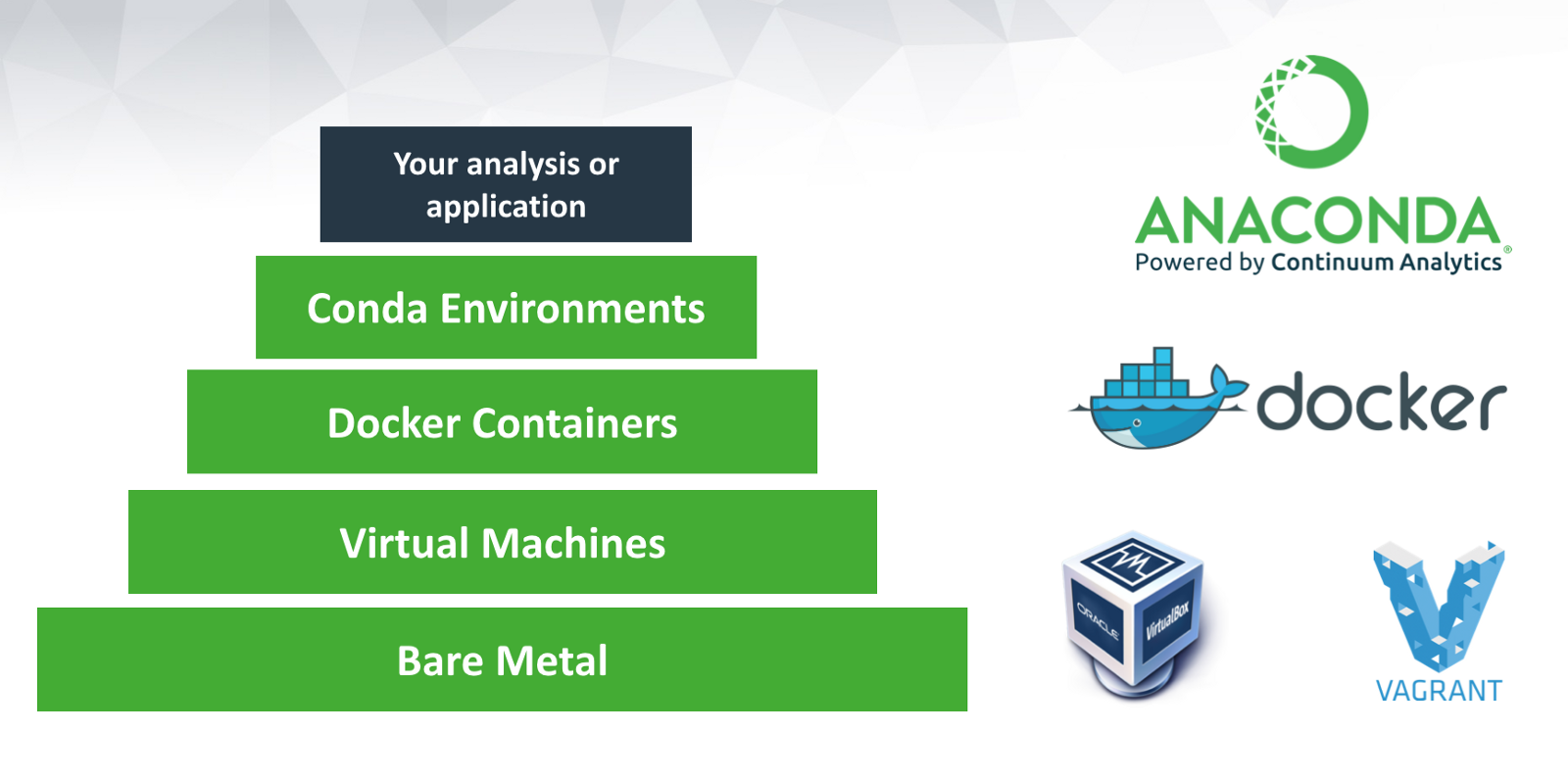

Docker is

a set of coupled software-as-a-service and platform-as-a-service products that use operating-system-level virtualization to develop and deliver software in packages called containers. The software that hosts the containers is called Docker Engine. It would be quite practical for you if you know why you want Docker and know about how it works.

Why would I want to use Docker?

Imagine you are working on Python and you send your code to a friend. Your friend runs exactly this code on exactly the same data set but gets a slightly different result. This can have various reasons such as a different operating system, a different version of Python, Tensorflow and so on. Docker is trying to solve these problems. And also a Docker container can easily be sent to another machine, you can set up everything on your own computer and then run the analyses on e.g. a more powerful machine. And you can send the Docker container to anyone (who knows how to work with Docker).

Basic concepts of Docker:

-

Containers

- Imagine you’d like run a command isolated from everything else on the system. It should only access exactly the resources it is allowed to (storage, CPU, memory), and does not know there is anything else on the machine. The process running inside a container thinks it’s the only one and only sees a barebones Linux distro the stuff which is described in the image.

- An important point to note: a container can run more than a single process at a time. Some people choose to limit it to one though. You could package many services into a single container

-

Images

- An image, is a blueprint from which an arbitrary number of brand-new containers can be started. Images can’t change (well, you could point the same tag to different images, but let’s not go there), but you can start a container from an image, perform operations in it and save another image based on the latest state of the container. No “currently running commands” are saved in an image. When you start a container it’s a bit like booting up a machine after it was powered down.

- When starting a container from an image, you usually don’t rely on the defaults being right - you provide arguments to the command being executed, mount volumes (directories with data) with your own data and configurations and wire up the container to the network of the host in a way which suits you.

-

Volumes

- having data persist is really useful. That’s where volumes come in. When starting a Docker container, you can specify that certain directories are mount points for either local directories (of the host machine), or for volumes. Data written to host-mounted directories is straightforward to understand (as you know where it is), volumes are for having persistent or shared data, but you don’t have to know anything about the host when using them. You can create a volume, Docker makes sure that it’s there and saved somewhere on the host system.

- When a container exits, the volumes it was using stick around. So if you start a second container, telling it to use the same volumes, it will have all the data of the previous one. You can manage containers using Docker commands (to remove them for example). Docker compose makes dealing with volumes even easier.

-

Dockerfile

- A Dockerfile is a set of precise instructions, stating how to create a new Docker image, setting defaults for containers being run based on it and a bit more. In the best case it’s going to create the same image for anybody running it at any point in time.

- In a Dockerfile, you usually choose what image to take as the “starting point” for further operation (FROM), you can execute commands (starting containers from the image of the previous step, executing it, and saving the result as the most-recent image) (RUN) and copy local files into the new image (COPY). Usually, you also specify a default command to run (ENTRYPOINT) and the default arguments (CMD) when starting a container from this image.

-

Docker compose

- I love this tool. In the beginning of Docker, you had to write lots of long-ish terminal commands. Especially if you wanted to have multiple containers talk to each other and do something useful.

- And that’s a simple, nice toy example, without environment variables. Also the container is already built. Just imagine huge multiline commands, with lots of parameters. Urgh.

For more information about Docker please read these pages:

Anaconda is

a free and open-source distribution of the Python and R programming languages for scientific computing, that aims to simplify package management and deployment. Package versions are managed by the package management system Conda.

Why would I use Anaconda?

Anaconda provides the tools needed to easily:

- Collect data from files, databases, and data lakes

- Manage environments with Conda (all package dependencies are taken care of at the time of download)

- Share, collaborate on, and reproduce projects

- Deploy projects into production with the single click of a button

Data scientists that work in silos struggle to add value for their organization. That’s why Anaconda created an integrated, end-to-end data experience.

I have searched a lot to find a page can guide me to install Anaconda on Docker from scratch. Finally I found this page quite useful. I highly recommend it if you want to create your own image on Docker.

Tag: Docker, Data Science, Anaconda, Installing

Comments